Our journey started in a cool, dark maloka (a communal house) in the indigenous community of Buenos Aires deep in the Amazon rainforest of Vaupés in Colombia. Jopo (toasted tobacco blown through the nose) and mambé (powdered coca leaf eaten slowly as a paste), receives a blessing of protection and permission for our trip from the Payé (shaman), and is passed down the bench in silence. As the dust of the jopo settled, the intricate masterwork of the maloka became clearer, making us wonder in awe at how this huge structure came to be; made entirely by hand from palm.

For the next six days we would understand how deep, interconnected systems of thinking, rooted in ancestry and developed over many centuries, allows communities to exist in this remote and unyielding place. The trip was organised by eco-ethno tourism specialists Colombia Oculta. We travelled along the Cananarí and Apaporis rivers with Yuruparí peoples, including numerous ethnic groups (Tucanos, Taibanos, Barasanos, Tatuyos, Cubano, Cabiyarí and Guananosto), witnessing sacred ceremonies and visiting the natural sites that feature in their cosmology. Beyond the beauty, ingenuity and immense strength of landscapes and communities, however, lingered the realities of life for a people with many needs not met, and a sense of their vulnerability to existential threats, whether brought by climate change or the creeping influence of modernity, particularly through social media.

Vaupés is the least populated department in Colombia but home to 27 groups who identify as indigenous. As well as being the heart of indigenous cultural preservation in Colombia, the Amazon rainforest in Vaupés is a stronghold of relatively untouched wilderness. Its location on the equator, where northern and southern rain patterns converge, creates a hydrological flow that feeds the Amazon river system, acting as a vital buffer against climate change globally and a refuge for biodiversity.

We were hosted by a family from La Comunidad de Villa Real by Juan Torres of the Taiwano ethnic group, his wife Elena, and their three children. Elena joined Juan’s community from her own further downstream when they married. Communities in Vaupés have a unique linguistic exogamy system which requires marriage outside of one’s ethnic group, to someone who speaks a different language. This promotes a stronger gene pool, unity between different groups and creates a vast network of shared knowledge on their environment, such as where to find certain plants, effective hunting paths and ways of navigating rivers.

We spent our first night in a hammock in the maloka of the Morrocco community, falling asleep to the low murmur of men and elders sharing stories between blows of jopo, which is said to “sweeten the word”, enhancing communication and harmonious dialogue. At 5am I woke to the sound of roosters and women cooking- indigenous communities have traditionally woken at dawn, something the Spanish forced to change in other areas. Looking at a tattered poster of the Global Sustainable Development Goals on the maloka wall and specifically goal 6, access to clean water and sanitation, made me consider the unpleasant ordeal visiting the toilet during the night, and our instruction to use as little water as possible to clean our hands, given the community don’t have rainwater harvesting infrastructure. Only 65% of Vaupés has access to clean water and insufficient wastewater management has led to increases in infections and diarrheal and respiratory diseases, especially amongst children (Rodriguez, 2022). Communities in the area are in the process of organising together to become a reserve (Resguardo indígena) which would grant groups legal title over the land, place stronger protections on land and help them attract funding and support for projects such as water and sanitation.

Somewhat surprisingly, we saw in this community and all others we visited mobile phones seemed to be more numerous than proper shoes. Our guide explained some upsides- tracking wildlife through apps like Merlin is one way mobile phones can be useful for the community, women who have left their families like Elena are given a way to communicate with them. However the elders shared concerns that the young people were distracted from community activities and duties…Access to social media will only increase- mobile signal is improving across the Amazon through infrastructure. With what we know about how the Western world is being trapped by dopamine hits and algorithmic manipulation, these portals to our rapidly changing world can’t look less of a threat to indigenous identity being eroded.

We set off to hike the Tepuy de Morocco — a billion year old precambrian tabletop mountain which forms part of the Guiana Shield (one of three cratons of the South Amercian plate). The steep, wet climb through a tangle of roots and thick growth was humbling, but not least with the speed at which Juan’s family took to the mountain in their crocs, Elena breastfeeding her baby in one arm, in another pots to cook with.

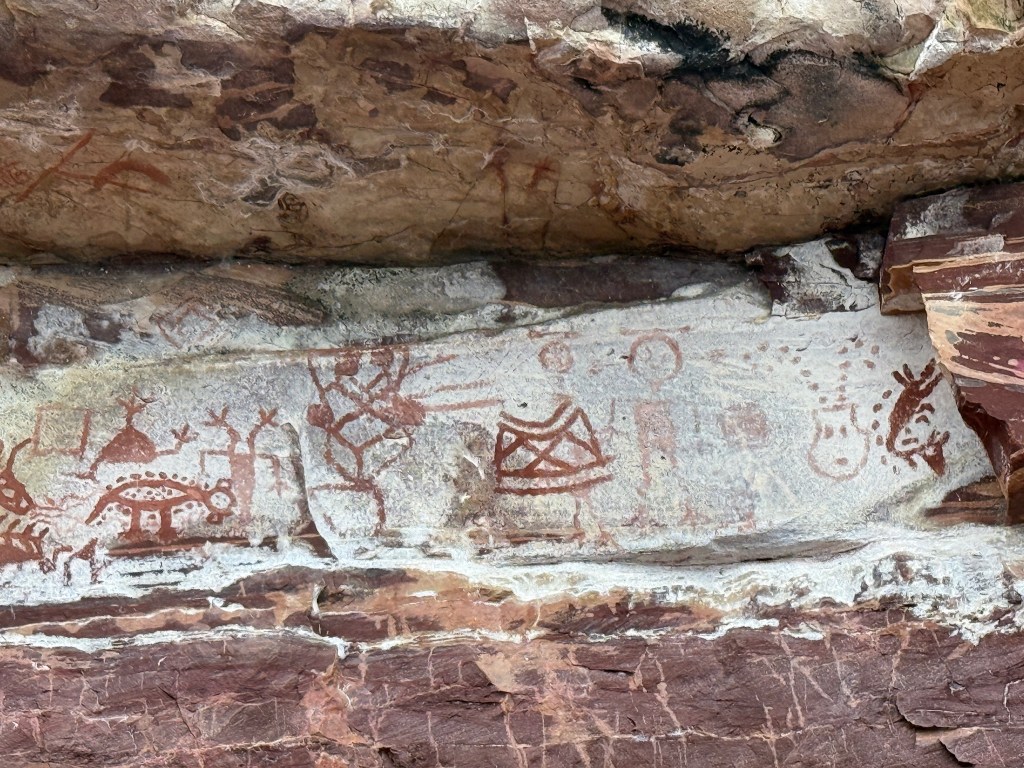

Monumental rock paintings wrapped around the tepuy’s steep cliffs, depictions of shamans, ceremony, animals and agriculture — some dating back 15,000 years. This tepuy is a sacred site believed to house their ancestors, for centuries communities would journey to the cliffs to worship them and collect macaw feathers for ceremonial dances, still used today. The astonishing preservation of such a long-standing tradition seems at odds with the little literature that exists about the tepuy and its rock paintings- Colombia is still discovering its indigenous art legacy.

As we walked we learnt of the many plants are used to provide remedies, food and materials to local communities, from snake venom antidote to breast pain reliever.

We camped on the summit tucked away from rain in a cave, and as day broke made our way to the La Ventana al Mundo (“The Window to the World”). A spectacular panoramic view of the vast rainforest brought a swelling of awe, making me think of the iconic ‘Blue Marble’ image of Earth taken by the Apollo 17 crew in the 70s, and how it shaped our perception of the planet.

The birds eye view of the forest gives a sense of how the land in Vaupés is being impacted by land conversion activities. Given its challenging terrain and remoteness, Vaupés has attracted relatively little mineral extraction or large scale agriculture compared to other departments in Colombia. The patches of cleared forest for ‘chagra’- small-scale subsistence farming- appear as modest openings in the vast expanse, regenerating areas indicated by the bright trunks of Yarumo trees; pioneer species that quickly colonise deforested areas. Communities grow crops on small plots for three to five years before allowing the land to regenerate. They manage nutrient-poor soils by using controlled burning to release essential minerals and incorporating biochar to enhance soil fertility and moisture retention.

After the descent we spent hours meandering in a small horse power canoe travelling to La Communidad de Villa Real, moving through the serene flow of the tannin-rich Cananarí with towerin, palms and vines along its banks. We travelled over the gurgling confluence of several rivers and into the Apapori, a tributary of the Japurá River, which eventually flows into the Amazon river. The Apaporis flows over layers of hard metamorphic and igneous rocks of the Guiana shield- granite, quartzite, and sandstone- carving out dramatic rapids and waterfalls.

The main conduit to the Yuruparí connection and alignment to the land, its seasons and their ancestral beliefs is the ancient dance of Kapi. Communities perform Kapi four times a year taking on themes including fish, wild plants, cultivated plants and the universe. We were invited to take part in a ceremony dedicated to the yarumo tree, which holds medicinal properties and is used to make mambe.Preparation took hours, late afternoon air filled with thudding of various wooden vestiges used to make the jopo, mambé and yagé (also known as ayahuasca; a sacred plant-based brew the community drinks for spiritual healing and visionary experiences). Elaborate macaw feather crowns were made by a young man working for weeks before in isolation, observing a strict diet of sacred medicines.

In the west, we associate coca leaves solely with cocaine. Wade Davis, an ethnobotanist and anthropologist has led much of the research on the nutritional and spiritual value of coca leaves in indigenous cultures in Colombia. He emphasises that coca leaves are highly nutritious, providing essential vitamins, minerals, and are a very mild stimulant. “coca have as much to do with cocaine as potatoes do to vodka,” (Magdalena: River of Dreams: A Story of Colombia, 2021). In reality, coca leaves are a vital staple of indigenous diets and traditions.

The following day a peaceful stillness blankets the community, and we were finally feeling the effects of five days sleeping in a hammock, not having showered and a diet we were not used to- lunch that day was jungle rat, which we accepted muffling any reluctance given it’s a delicacy.

Reflecting on the night before, I felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude to have been given an opportunity to observe and take part in such a sacred event. The ethical question about our presence there lingered- western visitors are influencing these communities whether we like it or not. Yet tourism is a vital income source for this community, without which they might be more tempted by extractive activities like mining. This places great importance on the sensitive and considered approach of organisations like Colombia Oculta. In a quiet conversation with Elena outside her home, whilst she macheted small palm fruits in her hands she struggled to answer my question about the future hopes she has for her children. I wondered whether this was more to do with indigenous peoples’ concept of time being more cyclical than linear, or an uncertainty about what the future holds for them in this world. She shared that her eldest was expected to become the community’s Payé- in this family indigenous wisdom and tradition will likely live on. Whilst grappling with the future might represent a risk to these communities to protect them from what may come, the Amazonian worldview which sees time and nature as fluid and ever changing could make them much more resilient and adaptable than us.

Karamakate: “How many edges does a river have?”

Film: Embrace of a the Serpent (2015)

Theo: “The river has two edges.”

Karamakte: “The river only has one edge…The one it left behind.”

How can we respectfully access indigenous environmental knowledge to combat nature loss and climate change while equipping them with awareness of modern threats like social media—without diluting their identity or imposing external values?

On our final day back in Mitu, we went birdwatching with a leader of the Cubeo people- a young, sharp minded and kind natured man who returned to his community after a year of soul searching, committed to steward his people’s future. The abundance of bird life dazzled us, he carefully recorded each spotted species in the Merlin app- toucans, kingfishers, herons- in between sightings sharing the history of the place we walked through and his plans to address priority issues of health and education for his people. Meeting this future leader, so committed to his tradition and community and able to combine deep ancestral wisdom with modern foresight, inspired a huge sense of optimism that our worlds can meet in a way that is positive, and that in this time his people can be both protected and empowered.

All photos and content approved by Colombia Oculta, though views are my own.